Mexico Room Art Museum Philly Mexico Painting Art Museum Philly

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art began planning its new Mexican Modernism exhibition more than four years ago, the organizers had no way of knowing information technology would open at the nadir of an ballot season marked past blustery talk of edge walls and "bad hombres."

That context couldn't have been far from museum manager and CEO Timothy Rub'south mind, though, when he called the landmark exhibition "timely for many different reasons: political, social and artistic."

"Today, it is particularly meaning to reinforce the bond of friendship and respect that connects our countries," agreed Maria Cristina Garcia Cepeda, general director of United mexican states'south Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA). Speaking in the Not bad Stair Hall at a preview of the show last calendar week, Garcia Cepeda said, "This exhibit has strengthened the ties of friendship, exchange and collaboration between our institutions and our countries. We celebrate that Mexico and the United States might become fifty-fifty closer through culture and fine art."

- Run across ALSO:

- Volume Review: Jon Ronson investigates Donald Trump'due south connection to a conspiracy kingpin

- As voiceover piece of work globalizes, the art form endures in Philadelphia — and proves lucrative

- Drexel students make video game version of paralympic sport for those with low vision

Whatever strides a single museum exhibition can make in healing the wounds created on this flavor's argue stages, "Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950" — organized by the PMA in conjunction with United mexican states City's Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes — stands as a significant overview of Mexican modern art in the first half of the 20th century and its dialogue with the contemporary fine art worlds of the U.Southward. and Europe.

Featuring more than 250 works by effectually 70 artists, including painting, sculpture, prints, drawings, photography, broadsheets and digitally recreated murals, the show traces the innovations of artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo and their compatriots from the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 through the dispirited reflections of the 1940s as exiled Europeans arrived, fleeing the spreading Fascism in Europe.

"What emerges," co-ordinate to curator Matthew Affron, "is an exciting chapter in the world history of modern art — a chapter that puts the big social, political and aesthetic questions of the early 20th-century front and heart."

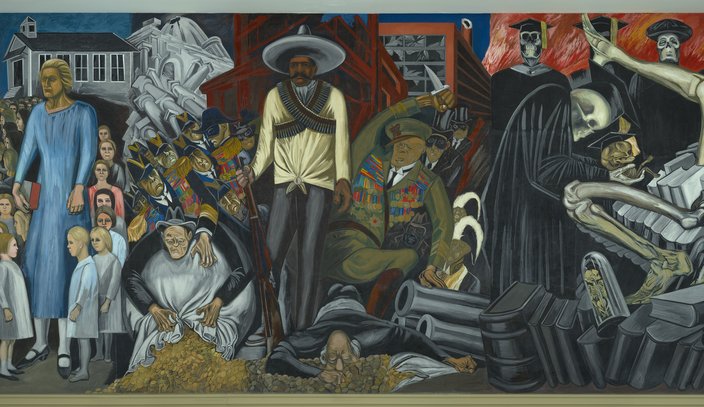

Jose Clemente Orozco/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York/SOMAAP, Mexico Urban center/for PhillyVoice

Jose Clemente Orozco/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York/SOMAAP, Mexico Urban center/for PhillyVoice

'The Epic of American Civilization' (wall mural particular), 1932–34, past José Clemente Orozco (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Deputed by the Trustees of Dartmouth College)

Somewhere around the midpoint of the exhibition are the 2 panels of Diego Rivera's "Liberation of the Peon" and "Carbohydrate Mill," which might look familiar to regular visitors to the museum. These two frescoes accept straddled the establishment's central staircase since 1943 when they appeared as part of "Mexican Art Today" – the last time such a comprehensive survey of the country'southward modern art was undertaken in this country.

In their usual places, however, the frescoes are sequestered behind glass and shrouded in shadows, giving their placement in "Pigment the Revolution," removed from their cases, the attraction of fresh revelation. The images positively shimmer from the glints of mica in the stone on which they're painted. But a more figurative new light is shone on them from their placement in the evidence, where they can be seen in the context of an evolving aesthetic, fusing the artistic and political upheavals of the day into a distinctive national style.

Specially in the earliest works in the exhibition, Mexican modernism'due south relation to the prevailing trends in the art of the early 1900s is obvious — paintings by Ángel Zárraga, the pseudonymous Dr. Atl, and the young Diego Rivera, then living in Paris, all evidence the strong influence of Picasso and the Cubists. Merely even at this nascent stage, the work is simultaneously rooted in Mexican folk art traditions. That influence merely grows stronger in the ensuing decades, as the armed conflict ends and the artists become part of the discussion on how to rebuild the state of war-torn nation.

Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York/for PhillyVoice

Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York/for PhillyVoice

'Liberation of the Peon,' 1931, by Diego Rivera (Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Cameron Morris, 1943-46-i)

The politicization of Mexican modernism is displayed in myriad forms throughout the prove, from Orozco's satirical paper cartoons and Goya-inspired grotesques to an entire wall of blaring propaganda prints created by left-wing groups in opposition to Fascism. Merely the fundamental component of that story is too the about challenging to translate into a traveling exhibition — the mural motion, whose all-time-known proponents are Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros.

The curators' innovative arroyo to that problem is to devote three massive digital screens to a landscape apiece by these masters, examining the works at near life size and providing interactive screens for visitors to get a closer look. By surrounding these replicas with the less grandiose art of these looming figures' less familiar contemporaries, the prove vividly conjures the full-blooded, passionate, obviously often conflicting arguments that must accept been ringing in the streets of Mexico at the fourth dimension, immortalized in vibrant visual forms.

Ultimately the show, like most idealistic revolutions, concludes on a note of disillusionment. A new generation has arisen, influenced past the surrealists and ofttimes critical of their predecessors' intimate ties with the post-revolutionary elite.

Meanwhile, these now elder statesmen are creating work of striking violence and despair — Frida Kahlo's work in this catamenia dwells on sadness and suicide, Siqueiros shows a monstrous demon infiltrating the church, while Orozco depicts cede and martyrdom. The final impression is of the friction betwixt impassioned vision and harsh reality, of an artistic revolution fought with more than enduring success than a political one.

Paint the Revolution:

Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950

Oct. 25-Jan. eight

Philadelphia Museum of Art

2600 Benjamin Franklin Pkwy.

Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Social club (ARS), New York/for PhillyVoice

Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Social club (ARS), New York/for PhillyVoice

'Self-Portrait on the Border Line Betwixt Mexico and the United States,' 1932, by Frida Kahlo (Colección Maria y Manuel Reyero, New York)

Source: https://www.phillyvoice.com/art-museums-new-mexican-modernism-revives-revolution/

0 Response to "Mexico Room Art Museum Philly Mexico Painting Art Museum Philly"

Post a Comment